Abstract

International climate change agreements typically specify global warming thresholds as policy targets1, but the relative economic benefits of achieving these temperature targets remain poorly understood2,3. Uncertainties include the spatial pattern of temperature change, how global and regional economic output will respond to these changes in temperature, and the willingness of societies to trade present for future consumption. Here we combine historical evidence4 with national-level climate5 and socioeconomic6 projections to quantify the economic damages associated with the United Nations (UN) targets of 1.5 °C and 2 °C global warming, and those associated with current UN national-level mitigation commitments (which together approach 3 °C warming7). We find that by the end of this century, there is a more than 75% chance that limiting warming to 1.5 °C would reduce economic damages relative to 2 °C, and a more than 60% chance that the accumulated global benefits will exceed US$20 trillion under a 3% discount rate (2010 US dollars). We also estimate that 71% of countries—representing 90% of the global population—have a more than 75% chance of experiencing reduced economic damages at 1.5 °C, with poorer countries benefiting most. Our results could understate the benefits of limiting warming to 1.5 °C if unprecedented extreme outcomes, such as large-scale sea level rise8, occur for warming of 2 °C but not for warming of 1.5 °C. Inclusion of other unquantified sources of uncertainty, such as uncertainty in secular growth rates beyond that contained in existing socioeconomic scenarios, could also result in less precise impact estimates. We find considerably greater reductions in global economic output beyond 2 °C. Relative to a world that did not warm beyond 2000–2010 levels, we project 15%–25% reductions in per capita output by 2100 for the 2.5–3 °C of global warming implied by current national commitments7, and reductions of more than 30% for 4 °C warming. Our results therefore suggest that achieving the 1.5 °C target is likely to reduce aggregate damages and lessen global inequality, and that failing to meet the 2 °C target is likely to increase economic damages substantially.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

UNFCCC Adoption of the Paris Agreement. I: Proposal by the President. Draft Decision CP.21 https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2015/cop21/eng/l09r01.pdf (United Nations Office, Geneva, 2015).

Nature Editorial Board. The maximum climate ambition needs a firm research backing. Nature 537, 585–586 (2016).

Hallegatte, S. et al. Mapping the climate change challenge. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 663–668 (2016).

Burke, M., Hsiang, S. M. & Miguel, E. Global non-linear effect of temperature on economic production. Nature 527, 235–239 (2015).

Collins, M. et al. in Climate Change 2013: the Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. et al.) Ch. 12 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2014).

Riahi, K., van Vuuren, D. P. & Kriegler, E. The shared socioeconomic pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Rogelj, J. et al. Paris agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature 534, 631–639 (2016).

Schleussner, C.-F. et al. Science and policy characteristics of the Paris Agreement temperature goal. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 827–835 (2016).

Rogelj, J., McCollum, D. L., Reisinger, A., Meinshausen, M. & Riahi, K. Probabilistic cost estimates for climate change mitigation. Nature 493, 79–83 (2013).

Hallegatte, S., Fay, M., Bangalore, M., Kane, T. & Bonzanigo, L. Shock Waves: Managing the Impacts of Climate Change on Poverty (World Bank Publications, Washington, 2015).

Dell, M., Jones, B. F. & Olken, B. A. Temperature shocks and economic growth: evidence from the last half century. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 4, 66–95 (2012).

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. J. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to US crop yields under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15594–15598 (2009).

Hsiang, S. M. Temperatures and cyclones strongly associated with economic production in the Caribbean and central america. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15367–15372 (2010).

Carleton, T. A. & Hsiang, S. M. Social and economic impacts of climate. Science 353, aad9837 (2016).

Deryugina, T. & Hsiang, S. M. Does the Environment Still Matter? Daily Temperature and Income in the United States. NBER working paper 20750 (National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, 2014); http://www.nber.org/papers/w20750.

Colacito, R., Hoffmann, B. & Phan, T. Temperatures and Growth: A Panel Analysis of the United States. IDB working paper IDB-WP-676 (Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, 2016); https://publications.iadb.org/handle/11319/7654.

Zhang, P., Deschenes, O., Meng, K. & Zhang, J. Temperature effects on productivity and factor reallocation: evidence from a half million Chinese manufacturing plants. J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 88, 1–17 (2018).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

O’Neill, B. C., Kriegler, E. & Ebi, K. L. The roads ahead: narratives for shared socioeconomic pathways describing world futures in the 21st century. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 169–180 (2017).

Burke, M. et al. Opportunities for advances in climate change economics. Science 352, 292–293 (2016).

Seneviratne, S. I., Donat, M. G., Pitman, A. J., Knutti, R. & Wilby, R. L. Allowable CO2 emissions based on regional and impact-related climate targets. Nature 529, 477–483 (2016).

Cai, Y., Lenton, T. M. & Lontzek, T. S. Risk of multiple interacting tipping points should encourage rapid CO2 emission reduction. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 520–525 (2016).

Hsiang, S. et al. Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States. Science 356, 1362–1369 (2017).

Hof, A. F. et al. Global and regional abatement costs of nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and of enhanced action to levels well below 2 °C and 1.5 °C. Environ. Sci. Policy 71, 30–40 (2017).

Mastrandrea, M. D. et al. The IPCC AR5 guidance note on consistent treatment of uncertainties: a common approach across the working groups. Clim. Change 108, 675 (2011).

Matsuura, K. & Willmott, C. J. Terrestrial Air Temperature: 1900–2010 Gridded Monthly Time Series (version 3.01) (Center for Climatic Research, Univ. Delaware, Newark, 2012); http://climate.geog.udel.edu/~climate/.

Tebaldi, C. & Knutti, R. The use of the multi-model ensemble in probabilistic climate projections. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 365, 2053–2075 (2007).

Balk, D. et al. Determining global population distribution: methods, applications and data. Adv. Parasitol. 62, 119–156 (2006).

Hartmann, D. L. et al. Observations: atmosphere and surface. In Climate Change 2013: the Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Stocker, T. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2013).

Stern, N. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2006).

Weitzman, M. A review of the Stern review on the economics of climate change. J. Econ. Lit. 45, 703–724 (2007).

Nordhaus, W. D. A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policies. (Yale Univ. Press, Yale, 2008).

Goulder, L. H. & Williams, R. C. III The choice of discount rate for climate change policy evaluation. Clim. Change Econ. 3, 1250024 (2012).

Arrow, K. J. et al. Should governments use a declining discount rate in project analysis? Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 8, 145–163 (2014).

Newell, R. G. & Pizer, W. A. Discounting the distant future: how much do uncertain rates increase valuations? J. Environ. Econ. Manage. 46, 52–71 (2003).

Groom, B., Koundouri, P., Panopoulou, E. & Pantelidis, T. Discounting the distant future: how much does model selection affect the certainty equivalent rate? J. Appl. Econ. 22, 641–656 (2007).

Greenstone, M., Kopits, E. & Wolverton, A. Developing a social cost of carbon for us regulatory analysis: a methodology and interpretation. Rev. Environ. Econ. Policy 7, 23–46 (2013).

Quiggin, J. Stern and his critics on discounting and climate change: an editorial essay. Clim. Change 89, 195–205 (2008).

Henderson, J. V., Storeygard, A. & Weil, D. N. Measuring economic growth from outer space. Am. Econ. Rev. 102, 994–1028 (2012).

Jean, N. et al. Combining satellite imagery and machine learning to predict poverty. Science 353, 790–794 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank L. Goulder, S. Hsiang and D. Lobell for comments. We thank the Erol Foundation for funding.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks R. Kopp and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions: M.B. and N.S.D. designed the research. M.B., W.M.D. and N.S.D. analysed data, interpreted results and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

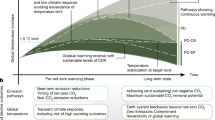

Extended Data Fig. 1 Discount rate scenarios used in calculation of cumulative discounted impacts of future warming.

a, Projected global average annual growth rates under SSP1 with and without climate change; estimates are averaged across bootstraps and climate models. Projected growth rates with climate change are used to define future consumption growth in Ramsey-based discount rates. b, Evolution of discount rates under different schemes through 2099. Ramsey-based schemes are Stern30, Weitzman31 and Nordhaus32, with corresponding assumptions about the pure rate of time discount ρ and the elasticity of marginal utility of consumption η shown in parentheses. Dashed lines are versions of these Ramsey-based discounting schemes that account for growth-rate uncertainty. Non-Ramsey schemes are Newell and Pizer35 and Groom36. c, Projected average annual growth rates separately for rich and poor countries under SSP1, with and without climate change. d, Corresponding Ramsey-based discount rates calculated separately for rich and poor countries, using income-specific growth rates from c.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Global GDP impacts can be negative at +1 °C but positive at +2 °C for some high-temperature-optimum bootstrap runs.

a, b, Country share of global GDP at baseline (a) and by the end of the century (b) under SSP1, assuming no climate change. c, Distribution of global GDP by temperature, under baseline (black) and the end of the century SSP1 without climate change (red dashed); absent climate change, a substantial portion of global GDP is projected to be produced in countries with hotter average temperatures. d, Climate-model-predicted average global warming under RCP2.6 by the end of the century (x axis) versus the correlation between country-level baseline average temperature and country-level predicted warming in each model. In models that warm less at the global scale, countries that are currently warm tend to exhibit relatively larger warming, while in models that warm more at the global scale, countries that are currently cool tend to exhibit relatively larger warming. Future impacts on global GDP are a sum of country-specific impacts, which are a function of where each country is on the temperature response function (Fig. 1a) and the projected amount of future warming in that country; a given percentage impact in a country with a large GDP has a larger effect on global GDP than the same percentage impact in a country with small GDP. For high-temperature-optimum response functions (for example, Fig. 1g), impacts can be negative at +1 °C but positive at +2 °C because (i) absent climate change, a much larger proportion of total global GDP is projected by SSP1 to be produced in countries that are currently warmer than the optimum, and (ii) climate models with lower overall global warming projections under RCP2.6 tend to have higher relative warming in countries that are currently warm. This generates negative impacts at about 1 °C, where impacts are dominated by negative effects in warm countries (largely in the developing world), but positive impacts at about 2 °C, where high-latitude countries instead warm disproportionately and experience benefits that outweigh the damages in tropical countries.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Change in cumulative global GDP under 1.5 °C versus 2 °C global warming by the end of the century under different discounting schemes.

Positive values indicate benefits (reduced losses) at 1.5 °C versus 2 °C. Each vertical line corresponds to a bootstrap estimate of benefits under each discounting scheme30,31,32,35,36. Red lines indicate median across bootstraps for each discounting scheme. Uniform schemes correspond to those in Extended Data Table 1; other schemes are described in Methods.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Robustness of results to alternative specifications.

Change in global GDP per capita in 2049 and 2099 based on regression models that include 0, 1 or 5 lags (a and b); bootstrap schemes that sample by country, five-year block or single year (c and d); or alternative SSPs (e and f). Top panels show percentage changes in global GDP per capita under 1.5 °C versus 2 °C; the bottom panels show change in cumulative global GDP in US$ trillions under a 3% discount rate.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Robustness under alternative warming paths.

Benefit—in terms of per capita GDP (a) and cumulative GDP (b)—of 1.5 °C versus 2 °C by end of century under the baseline assumption that overall projected warming occurs linearly between the baseline year and 2099 (pink), versus projected benefit assuming that all projected warming occurs by 2049 and temperatures remain constant thereafter (blue). Both scenarios have the same projected global warming by the end of the century. For the same level of overall warming by the end of the century, scenarios with rapid initial warming worsen the overall impacts of climate change and increase the cumulative benefits of limiting warming to 1.5 °C versus 2 °C.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Projected change in global GDP (%) under global warming by the end of the century, for each SSP.

Panels a–e show the change in GDP for different climate models under different RCP forcing scenarios, relative to a no-warming baseline (median bootstrap) for SSPs 1–5, respectively. Results are as in Fig. 4a, but for each SSP. Each dot represents an RCP-climate model projected change in global GDP under a given SSP; colours represent the four RCPs. Lines are least-squares fits to the points corresponding to the different RCPs with matching colour scheme. The three vertical black lines denote the 1.5 °C target, the 2 °C target and the median-estimated warming expected under current Paris commitments (2.9 °C)7. Warming is relative to pre-industrial levels.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Burke, M., Davis, W.M. & Diffenbaugh, N.S. Large potential reduction in economic damages under UN mitigation targets. Nature 557, 549–553 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0071-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0071-9

This article is cited by

-

Global spatiotemporal optimization of photovoltaic and wind power to achieve the Paris Agreement targets

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Reconciling widely varying estimates of the global economic impacts from climate change

Nature Climate Change (2025)

-

Social cost of carbon under endogenous social adaptation

Climatic Change (2025)

-

The impact of the European Union emissions trading system on carbon dioxide emissions: a matrix completion analysis

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

The economic commitment of climate change

Nature (2024)